Hello Chipmunks

I don’t know if I went through a teddy bear stage but at six I was definitely thrilled by chipmunks. At that time we lived in a private house that backed onto a wooded area full of pine trees. It was a big enough space to feel like a forest to me. And while running through our backyard there were regular sighting of a small and adorable striped creature. I did try to trap one using a cardboard box held up by a stick. Whether I tried to use anything reasonably enticing as bait, I no longer remember but I never managed to have a chipmunk for a pet.

Years later traveling on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, I remember seeing people feeding a multitude of chipmunks who were clearly begging for a handout. Considering that you regularly see signs in the national parks to not feed the animals, it is probable that you can, in fact, train any animal to approach for food. I was reminded of the time that I had taught a squirrel – a rodent in the same family as chipmunks Family Sciuridae – to gradually approach me for peanuts until it was willing to take one directly from my hand.

In any case, although we have lived in Riverdale over fifty years I had never seen a chipmunk anywhere in this neighborhood before. And now, I have several of them running through my backyard!

Chipmunk History

The name chipmunk seems to be of Amerindian origin possibly from the word chetamnon, the name given to it by the Chippewa/ Ojibwa Indians and meaning red squirrel. The current spelling, however, can already be found in books from the 1820s.

Our common eastern gray squirrel separated from the chipmunk ancestors in the Oligocene Epoch (33.7-23.8 million years ago). Although the three chipmunk lineages Tamias, Eutamias and Neotamias strongly resemble each other, they diverged into those three genera by the late Miocene (11.6-5.3MYA). There is only one living representative of the Eutamias, the Siberian chipmunk (Eutamias sibiricus) but there are about 23 species in the Neotamias which are found mostly in the Western United States. There is only one living species today in the genus Tamias – the eastern chipmunk (Tamias striatus). This is my new neighbor.

Chipmunks are clearly very colorful. The eastern chipmunk has one gray/black stripe going from the nape of the neck down the back and fading a bit as it travels down the tail. One each flanks there are two black stripes sandwiching a white stripe and two white lines one above and one below each eye. The adult chipmunk is between 5-6 inches long with a 3-4 inch tail. The other species show some differences.

Foragers

The genus name Tamias comes from the Greek meaning steward or housekeeper because of the chipmunks’ role in plant dispersal as they collect seeds in the fall and store them in various underground locations for use during the winter. Many of those seeds will germinate and those that are forgotten will be the source of new trees and other plants. Animals that have multiple locations for saved food are called “scatter hoarders.” Gray squirrels and blue jays are other examples of scatter hoarders. I have often wondered how squirrels find their own buried seed. One source claims that the animals licks the acorn before burial, and can later locate the site through scent. Unfortunately, other squirrels can also smell the saliva which is not apparently unique and only recognizable by one animal, and then raid the cache.

While plant foods such as seeds and nuts, berries , fungi and fruit comprise the bulk of their food, chipmunks will also eat insects and their larvae and other small organisms including small birds, frogs and snakes. Their mouth pouches make handy carrying basket for transporting large quantities of food back to their burrows. Beech nuts are a special favorite and nests have been found to contain 5,000-6,000 nuts by the beginning of autumn.

Life Cycle

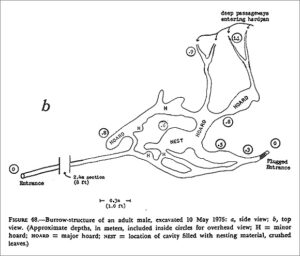

Burrows may be dug by the chipmunk although there is much evidence that most chipmunk burrows are actually dens dug and abandoned by other animals and then taken over by chipmunks. These burrows have locations for nesting and storing food. Some rodents even have defecation toilets if you will – tunnels where waste products are kept separately and when full are closed off. Seemingly chipmunks do not make such provisions.

Generally there are two litters per year , each containing 2-8 young, born after a 31 day gestation period. The first litter arrives April/May and the second July/August. The newborns are about 2.5” long and are hairless and blind at birth. By six weeks the mother allows them out of the burrow under watchful eye and by seven weeks she is more aggressively pushing them “to grow up.” By nine weeks she does not allow them to reenter their own burrow, forcing them to find their own quarters. The babies become sexually mature during the spring or summer following their birth. The father plays no part in rearing the young.

Despite being solitary except during mating season, chipmunks do vocalize and communicate with other chipmunks. Scientists fitted some with tiny microphones and recorded three kinds of calls which do indicate a certain amount of chipmunk- to- chipmunk interaction. One call warns intruder chipmunks against territorial invasion, another warns of an aerial predator while the third warns of a terrestrial predator. Chipmunks are themselves prey animals being eaten by owls and hawks, foxes coyotes and raccoons among others.

While it seemed a good idea at the time, I do not think I will try to tame any chipmunks in the coming spring!

For more of my writings, check out my book A Habit of Seeing: Journeys in Natural Science.