Rosh Hashannah and Honey

Rosh Hashanah and the Jewish holiday season are now almost two months behind us. Most of my blog topics are the result of some subject or natural occurrence that caught my interest. However, if there is a natural history tie-in with one of the holidays, I like to highlight that in a timely fashion.

This year I had decided that I wanted to explore the details of honey making but could not find the time before Rosh Hashanah was upon us. Time was flying. Yom Kippur came and went and then Sukkot was upon us. The Hamas invasion of southern Israel will forever complicate our relationship to Sukkot 2023.

Under normal circumstances, our family custom is to use honey instead of salt when breaking bread as we sit down for these holiday meals. The apple so closely associated with Rosh Hashanah is also dipped in honey. The symbolism is clear; we are looking forward to a Sweet Year. If possible, I always try to use wildflower honey from Israel.

Speciality Honeys

Notice, I said wildflower honey. Over the years I have had the opportunity to try various specialty honeys such as chestnut and avocado honey. Bees do not take instructions from their hive keepers, so bees gather nectar where they will. However, if the hives are in an area with a preponderance of a particular flowering plant, the honey will contain a larger percentage of nectar from those flowers. Many of those specialty honeys are darker and less sweet without having – to my palette – any greater attractiveness in flavor. In fact, I recently saw mention of a beekeeper who said that spring honeys were lighter in color and sweeter than the honeys produced later in the season. In the end, we may be saying the same thing.

Gathering Nectar

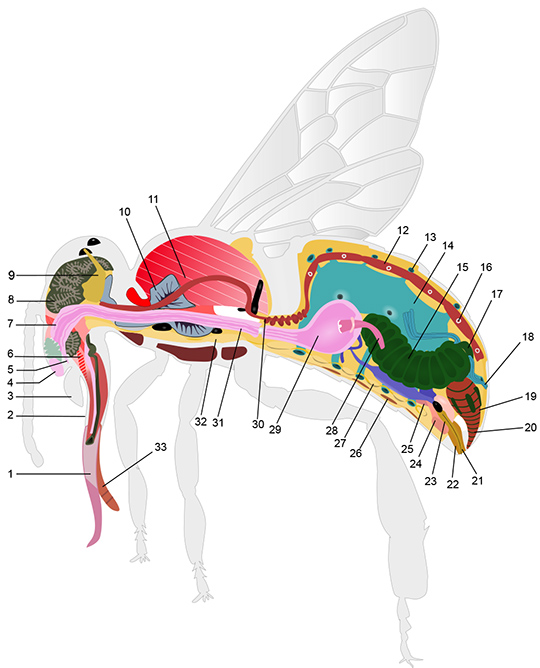

It is my experience that if you move slowly you can watch honeybees up close as they move from flower to flower harvesting nectar and pollen. Nectar is collected through a straw-like tongue called a proboscis. The nectar is sucked up and ends up in a second stomach called the honey stomach or honey crop and can hold about 40 mg of nectar and requires visiting 1000 flowers over the course of an hour. This represents about half the weight of the bee itself. If a bee needs energy, she will draw on some of the nectar it has stored in the honey crop.

Turning Nectar into Honey

Flower nectar has a water content of 70-80% while honey’s water content is about 18%. Digestion of the nectar’s sugars begins in the honey crop of the foraging bee with the end products being the simpler sugars glucose and fructose. When the bee returns to the hive, it regurgitates the nectar to the hive bees. They, in relay groups over twenty minutes, regurgitate it by forming bubbles, passing it along from one group member to the next. This bubbling increases the digestion and the concentration of the nectar. However, at the end of this process, the water content is still high at 70% and this proto-honey is placed in the honeycomb although the cells are not yet capped.

Bees can create large amounts of body heat and the hive temperature in the honey working area is around 95 degrees F. Bees need to reduce heat by fanning. Bees also fan the open honey cells with their wings and the proto-honey loses water through evaporation. When the water content is reduced sufficiently, the honeycomb cells are capped.

So What About the Pollen?

Anyone watching a foraging bee sees the collection of pollen usually around the hind legs, sometimes under the stomach. While honey is a delightful addition to our diet, the real value of foraging bees is their role in pollination. Pollen is the male gamete necessary for the formation of seeds. Without pollinators, pollen would be largely locked onto a single flower instead of being spread around to other flowers of the same species.

The process of collection is quite interesting. As bees fly through the air, their body surface becomes positively charged. As they land on a flower’s petals, the pollen is attracted to the entire body. The bee uses its legs to wipe the pollen down to the stiff hairs on the abdomen or back legs. These tufts are called scopa (from the Latin meaning a broom)while the collections are sometimes called pollen baskets or corbiculae (from the Latin meaning a basket).

The bees are not just volunteers helping flowers reproduce. The bulk of the pollen is mixed with a bit of nectar into pellets called bee bread. Each pellet may contain as many as 160,000 pollen grains. It is brought back to the hive and scraped off the hind legs into honeycomb cells. While honey is a high energy food source, pollen supplies protein both for the adults and the growing larvae.

Although honey is readily available to today’s consumers, it should be noted that only 4% of the 20,000 bee species actually make honey. For the honey we enjoy we have to thank Apis mellifera which is not even native to the Americas.

If you have enjoyed this piece, let me recommend my book A Habit of Seeing: Journeys in Natural Science.

As always, I enjoyed this immensely! With so much information and your “sweet” style…all it was missing was an actual piece of challah! May the news from Eretz Yisrael improve in its sweetness.